The award recognizes and acknowledges those who have made a major contribution to the world of Indonesian dance. The award can be given to individuals or groups, both living or posthumously.

Marzuki Hasan & Nurdin Daud:

Half a Century of Stunning the World with Acehnese Dances

By: TItah AW & Linda Mayasari

Among the diversity of Indonesian traditional dances, there is a number that never fails to get the audience to hold their breath while their minds glued to its dynamic beats – unified and intense. Powerful, yet elegant. The number is Acehnese sit-down dance, known as Saman.

Foto Pak Nurdin mengajar tari di Amerika

(Dok. Arsip: Zuraida Nurdin; istri Pak Nurdin)

Foto Pak Marzuki & Pak Nurdin dan kontingen tari Indonesia di American Dance Festival

(Dok. Arsip: Zuraida Nurdin; istri Pak Nurdin)

If you ever encountered Saman on any stages, or even learned it even though you were not a native to Aceh, then you have Marzuki Hasan and Nurdin Daud to thank.

For the past 50 years, the two Aceh-born dance maestros have played a crucial role in introducing Acehnese dances and made them known across Indonesia and overseas. Beyond that, Marzuki Hasan and Nurdin Daud have made significant updates both in the structure and tradition of Acehnese dances, that they could appeal to a wider audience, especially the younger generations.

“When little, the boys at the village and I used to live at the meunasah (a religious learning centre at the local mosque). That was when we learned to recite poems and verses reciprocatively,” the 81-year-old Uki – as Marzuki Hasan is fondly known – said. As a native Acehnese, they breathe poems, verses, and dances. From young until adulthood, both Marzuki and Nurdin kept learning at Meunasah, as well as other competitions. “Creating a poem or verse is a spontaneous act, a natural gift that we live with. It just flows,” Marzuki continued.

They started introducing Acehnese dances in 1970s, when they met at Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), which had only been opened for two years at the time. Back then, Marzuki has just finished his study in Yogyakarta and decided to focus on the arts scene, while Nurdin had just arrived in Jakarta. At the time, Acehnese dances were not closely as popular as others from Java and Bali. But they finally found the right exploration space when they met as Seudati dance teacher at Lembaga Pendidikan Kesenian Jakarta (LPKJ), which we would later know as Institut Kesenian Jakarta (IKJ). Slowly but surely, their love and consistency in exploring Acehnese dances started to bear fruits.

In Aceh, dances, poems and verses are celebrated, but they are constrained by local norms and Sharia law. When they relocated to Jakarta and gained some freedom to develop their artistry, Marzuki and Nurdin did significant exploration and modification in structure, movement, collaboration, and dramaturg in the dance shows. For example, they put male and female dancers on one stage for a Saman performance. This is a big taboo in Aceh. “Note that we put them together, but not mix them. It stirred some controversies, but recently since Aceh practiced Sharia law, we can no longer do that, so we follow the local customs,” said Marzuki.

Foto Pak Marzuki & Pak Nurdin saat diundang pertunjukan di Australia

(Dok. Arsip: Zuraida Nurdin; istri Pak Nurdin)

Koreografi Pak Marzuki di Galeri Indonesia Kaya

(Dok. Arsip: Djoko)

In 1978, between teaching schedules, they created Rampa dance when they were still active in the Cakra Donya group. The dance, which is originally 75-minute long, is what we currently know as Aceh Rampai dance. Marzuki and Nurdin have consistently developed the movements of Saman, Ratoh, Seudati, Laweut, and other Acehnese dances. The creative process was usually divided between them based upon expertise. Marzuki, who was more active in poems and verses created the accompanying music and lyrics, while Nurdin created the choreography and dance structure.

People slowly started to grasp the beauty of this traditional dance, which was heavily influenced by the Malay culture. “The characteristics of Acehnese dance are very distinctive. Its core lies not in the wiraga-wirasa-wirama (physical-sense-rhythm) as in Javanese and Balinese dances, but in its unity, power, discipline, and bravery,” said Marzuki. He continued, “There are two dominant parts in it, the movement and the vocal. In Acehnese dance, whatever can turn into music – the musical body, the musical vocal, even the floor can be a musical instrument.”

Marzuki believes, although constrained by Acehnese cultural rules, there is room for exploration. In verses for example, Marzuki composed many new lyrics, even some were created spontaneously. They don’t only serve as prayers, the lyrics in Acehnese poetry sometimes contain stories, wisdom, advice, religious guidance, and even social critics. “I once stood to lead a strike and deliver an oration, but using poems and verses. That was soo memorable, because it showed how strong and versatile this tradition was.”

The exploration in creating new Acehnese dances was then brought into American Dance Festival 1984. Not only did it mesmerize the audience, the performance also opened doors for Acehnese dances to be performed at various global festivals and stages. Since then, both Marzuki and Nurdin engulfed themselves in teaching, choreographing, and travelling to different parts of the world, exploring America, Africa, Australia, Europe, and many regions in Asia. They also regularly performed in the national palace, as well as events like Ganefo, SEA Games, and PON. “Between the 1980s and 1990s, I rarely got a break. I was busy travelling the world. But I am so proud of bringing Acehnese dances to places,” he reminisces in fondness.

Not only in the professional dance scene, Acehnese dance also grew popular as an extracurricular activity in high schools around Jakarta and its neighbouring cities. According to Marzuki, the phenomenon started with IKJ’s arts program, which organized performances around schools in 1990s. Since then, Acehnese dances gained popularity, there was even a weekly Acehnese dance festival. The height of Acehnese dances in Jakarta made way for new modifications in movement, costume, poem, verse, and the tradition itself. Marzuki and Nurdin could see that their determination had enabled a major wave of creativity within Acehnese dances.

Brosur ke Riyadh (3)

(Dok. Arsip: Zuraida Nurdin; istri Pak Nurdin)

Brosur ke Riyadh (2)

(Dok. Arsip: Zuraida Nurdin; istri Pak Nurdin)

Foto Pak Nurdin sebelum vakum dari dunia tari

karena mulai sakit

(Dok. Arsip Zuraida Nurdin; istri Pak Nurdin)

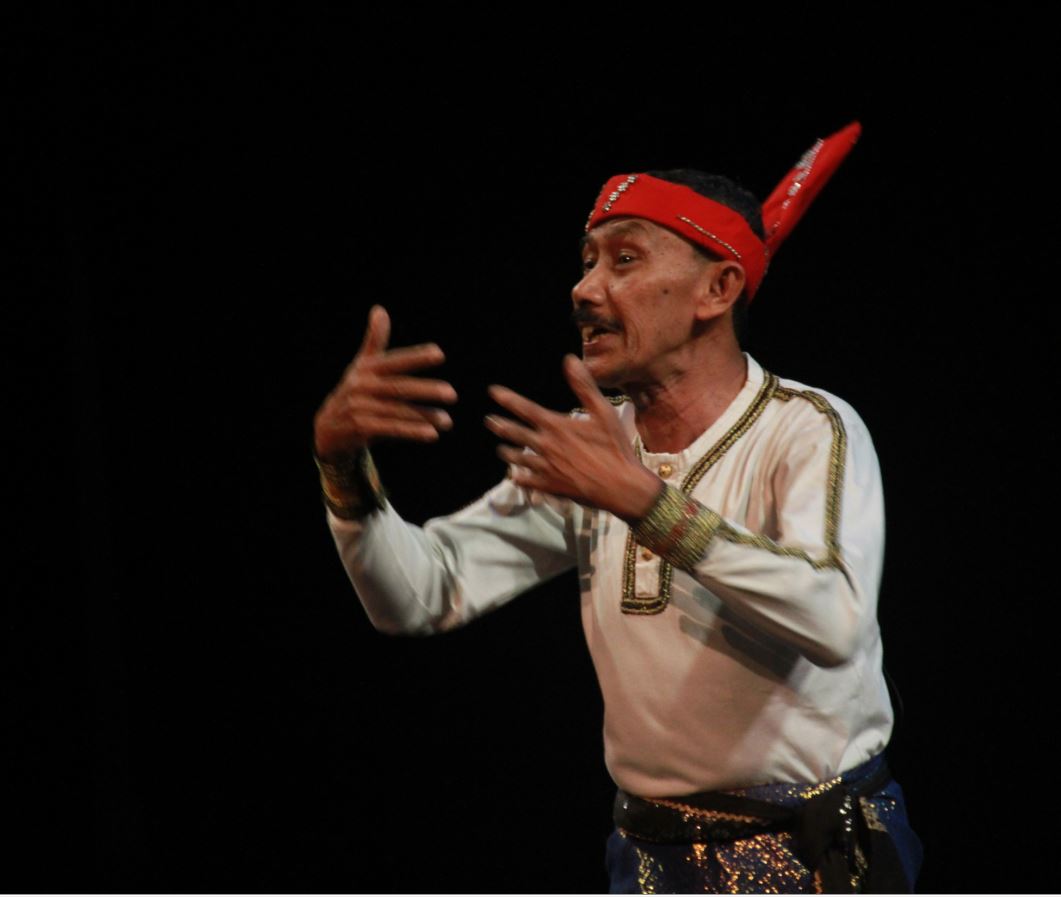

Pak Marzuki dalam salah satu aksinya memimpin tari Aceh

(Dok. Arsip Djoko)

Unfortunately, their activities slowed down since Nurdin fell sick in 1990s, up to his passing in 2007. Even then, the mission to preserve Acehnese dance continued with Marzuki and the new generation of dancers.

The Lifetime Achievement Award at IDF 2022 is awarded to both of them, for lives dedicated to preserve and the unceasing effort to update Acehnese dances, as well as making way to bring the dances to their public of various cultural backgrounds.

Thanks to Marzuki and Nurdin, the Acehnese dance tradition that they encountered in the mosques near their houses, can now be appreciated by the global audience. Their practice in Acehnese dances have become a source of inspiration for the next generation of Acehnese dance artists to elaborate or offer new interpretations to the diversity of its artistic tradition, and for dance artists in Indonesia to see tradition and culture in a more open and conversational way.

When many traditional artists keep to the rigid or sacred rules of the artistry that may make them out of date, Marzukii and Nurdin had bravely used critical and creative approaches that made traditional artistry, especially Acehnese dances, stay relevant. That is also why the artistry stays alive and celebrated by many.